Richard Bates began his apprenticeship at The British Clockmaker, INC in July 1996 where he learned from Master Clockmaker Ray Bates. He finished his Apprenticeship in July 2001. He became a Master Clockmaker in July 2010. In the Autumn of 2019 Richard became the President, and sole Owner of The British Clockmaker, INC.

Richard Bates began his apprenticeship at The British Clockmaker, INC in July 1996 where he learned from Master Clockmaker Ray Bates. He finished his Apprenticeship in July 2001. He became a Master Clockmaker in July 2010. In the Autumn of 2019 Richard became the President, and sole Owner of The British Clockmaker, INC.

In the many years since he began his Journey as a Clockmaker Richard has restored many hundreds of Museum Quality Antique Clocks, Automata, Swiss Musical Boxes, and Marine Chronometers, under the Expert Mentorship of Master Clockmaker Ray Bates.

When asked what some of his favorite things about being a Clockmaker are, Richard answered “the process of dismantling a 200 year old or older clock is always an exhilarating experience. The beauty of the hand painted dials, with unique scenes painted into the corners and on the upper sections are wonderful to behold. Removing the dial to reveal the expertly crafted clock movement behind. Dismantling all the levers, and gears which were hand crafted by a Master Clockmaker from two centuries earlier. Carefully cleaning and then slowly and methodically repairing all the wear and tear from running the clock over that amount of time.

When all the repairs have been completed, and the clock has been thoroughly tested, and the clock is ready to go home it is a pure joy to see the owners happy faces, that’s a priceless moment. I never grow tired of the restoration process, the personal connection to the clock, the owners of the clock, and the original Maker.

It is always a wonderfully satisfying thing to be able to reanimate these works of art built many hundreds of years ago. It’s a testament to the original Clockmaker’s abilities that these clocks can be put back into mechanical shape again to run another couple of hundred years more, It’s remarkable actually! “

Richard added “ To have the skills to be able carry on this many hundreds of years old Craft is a privilege and an honor. I was fortunate to have been taught by such a Master Clockmaker, Mentor, Father, and Friend.”

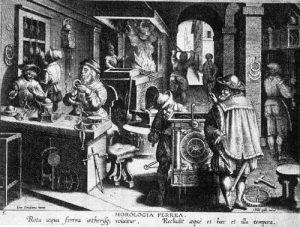

From an engraving from Johannes Stradanus

and Boley watchmaking lathe

Ray Bates sits in a room surrounded by clocks. They rest on the floor, line the shelves, and hang on the walls of his shop in Newfane, Vermont. They are museum-quality works of art. Rich in decorative hand work – engraved and cast and exquisitely painted – these silent pieces of clocks, surrounded by their functional brethren whom Bates has brought back to life, serve to remind the clockmaker that his job is not to “fix” antique and high quality timepieces, but rather to re-animate them.

The British Clockmaker at work “I actually do make clocks,” he admits, “as I did to earn my Master Clockmaker status in Scotland, but that now is irrelevant. The function of a mechanical clock nowadays – in a world of television, satellites, and digital and quartz timepieces – takes on new significance. Now, it serves more to remind us of the ingenuity and art that once routinely went into the making of practical objects, and the timelessness of real quality.”

“My mission, as I see it, is to save as many of these antique clocks as I can, to bring them back to their original mechanical integrity – using all of the same techniques and materials from their period – and hope that someone will maintain that tradition long after I am gone.”

Bates grows animated as he shows the inner workings of a particularly complex clock. “One of the things that impressed me most as an apprentice was being taught that every time we replaced something in a clock, our work should be indistinguishable from that of the original maker – not just in style of workmanship, but in the actual metal formulation as well. Now, as I work on a piece, I feel I”m side by side with the craftsman who made it.”

Learning to “do a good job” has taken The British Clockmaker some considerable time and effort. Upon graduation from high school he entered a five-year apprenticeship with the R.L.Christie clockmaking company of Edinburgh, where he learned the craft in the centuries-old traditional manner, under the tutelage of European masters. He also concurrently studied mechanical engineering at the University of Edinburgh and graduated from both programmes as a Craft Member of The British Horological Institute, London. Completion of his “masterpiece” clock earned him his Master Clockmaker status in 1952.

“I really am in a kind of time warp,” he says, “because I am one of the few people still practicing today using the techniques that were current three hundred years ago, and rarely still being taught since the breakdown of the apprenticeship system more than 25 years ago.”

After two years in the Royal Air Force as an instrument engineer and photo analyst, and several more working in London where he started his own business, he became impatient with the pace of British business and society. It was then, with ten job offers from everywhere from the West Coast, Mid-West, the South, and New England, he moved to America. He soon set up in business in Boston, then moved with his American wife, Beverly, and growing family of three sons, to Newfane, Vermont in 1964.

A somewhat dilapidated old inn in the village became their new home. The clock shop was located in what had been the bar and it was several years before the occasional old bar patron could be convinced of the change in its function! Bates commuted every month to Boston to service his clientele there and would return with work to keep him busy for another month.

In time, more and more business came to him from all over New England and further, and institutions and museums entrusted their finest clocks to his care; Harvard, Mystic Seaport, Old Sturbridge Village, Dartmouth College, Boston Atheneaum, Dudley Observatory, among them.

Following the traditional system which had nurtured his learning and skills in his native Britain, Bates designed and established an apprenticeship programme, in conjunction with the State of Vermont, in 1966, and several apprentices passed through, under his scrupulous guidance, to become journeyman clockmakers, and with one becoming a Master Clockmaker. “It was considered incumbent upon a Master Clockmaker to perpetuate the craft through his apprentices, and to encourage the highest standards of workmanship by example,” Bates points out. “and not every candidate made the grade.” His latest and current apprentice is his youngest son, Richard, who has joined him in the business and will eventually become a partner.

He laments the proliferation of tinkerers and self-styled clock repairers who commit acts of often irrepairable vandalism, and who take no professional responsibility for their workmanship. ” I estimate that I spend fifty per cent of my time undoing the damage these “butchers” inflict on fine clocks.”

Ray Bates is also a fine photographer, a member of ASMP, and has compiled a record of the most important clocks that have passed through his hands. Such makers as Willard, Tompion, Mudge, Knibb, Frodsham, Wilder and Wagstaffe head the list of what he hopes will be a book illustrating the best of more than three centuries of clockmaking.

The top of the hour arrives in the workshop, and the walls reverberate with the chiming of dozens of healthy, beautiful, occasionally exotic, restored clocks – a happy reminder that business now comes to his doorstep. Ray Bates smiles amid the musical chaos – a man happily embarked on his mission.

“Robertson Davies wrote a fictional piece about a clockmaker,” he says, “which might as well be a description of my experience. In it, he wrote, and I”ll quote in bits and pieces, ” It is never easy to find people who can be trusted with fine old pieces, because it calls for a kind of sympathy that isn”t directly hitched to mechanical knowledge. With these old clocks you need to know not only how they work, but why they are built as they are…so the real task is to discern whatever you can of the maker’s temperament and work within it…and persuade it to come to life again.”